Hidden History – Glimpses of Jane Austen’s Regency London

On the town

The Detour

The Regency Period and those who write about it both in non-fiction and fiction have provided me and others like me with a pathway to escape from the day to day chores, the supermarket jingles and in my case Dartmoor’s dark wintery days. The ones that are filled with icy drizzle, musty, dank smells and winds that rattle all windows that aren’t double glazed.

What is the charm of the Regency world that entices us away from our lives today? Perhaps it is that it was a time of contrasts? Elegance and sordid ugliness in cities lay only a few streets apart from each other. Witty conversations and satirical cartoons, inventions, scandal, popular literature, gentlemen’s clubs, travel and countless forms of entertainment enlivened the lives of the ‘ton’. While gin dens, prostitution and poverty were the flip side of the ‘farthing’ in urban areas.

It is a time that has been used by novelists as varied as Georgette Heyer, M.C. Beaton, Naomi Novik, Patrick O’Brian, Julian Stockwin and C.S. Forester as a backdrop against which they have unfolded their engrossing stories.

Devotees of Jane Austen’s novels would agree that with keen observation and wit she has left her readers a historical treasure trove of details about the society and times in which she lived.

Chance led me to a charity shop where I stumbled across a book of Austen related walks one of which focused on the places in London mentioned by Jane Austen in her novels or associated with her and her family. So, with my son coerced into holding the book while I tried to take photos we set off to discover the visible remains of Austen’s London.

The book proved to be slightly out of date, but undaunted we completed the walk that was described as ‘about five miles’, but ended up as over eight. This was due to various detours down ‘interesting’ streets often having sited places to stop for coffee and cakes. Unfortunately, Gunter’s Tea shop is no longer in Berkley Square. It was originally located in Nos 7 and 8 Berkley Square, but was demolished in 1936/7. However, the day of our walk was chilly and not suitable for one of their famed ices or sorbets.

Fortnum and Masons

Before setting out on the walk we popped in to Fortnum and Mason, which although not part of the suggested walk seemed an appropriate place to begin. Having first opened its doors in 1707 and as such would have well-known during the Regency period. By 1761 Charles Fortnum, Grandson of the William its founder started introducing speciality items for sale such as prawns and game in aspic jelly and during the Napoleonic Wars officers ordered ‘packaged supplies’ from them.

Perhaps Jane even sampled one of the Scotch Eggs that Fortnum and Mason are reputed to have invented in 1738. The hard-boiled egg wrapped in cooked sausage meat and coated in bread crumbs was perhaps today’s fast-food equivalent for long distance carriage and coach journeys.

The narrow wooden staircase that leads to its upper floors provides a tantalising taste of what the aristocratic shopper or their servants might have experienced and the scent of loose tea mingled with crystallised fruits fire the romantics imagination as to ‘what might have been’.

It is nice to imagine that when Jane went to London she might have called in to Hatchard’s bookshop, which has been in Piccadilly since 1797. It was established by John Hatchard a young bookseller, who started to sell books in London’s coffee houses at a very young age. The shop started at number 173 Piccadilly, but in 1801 moved to Numbers 189 t0 190 because the old shop was replaced by the Egyptian Hall. The street number was changed in 1820 to 187, but it is still the same place it was 1801, which may explain the creaking stairs as you walk up them. A portrait of John Hatchard monitors your ‘perambulation’ up the stairs and around the shop with an intelligent and amused glint in his eyes.

Jane stayed in Covent Garden with her brother during summer 1813 and again in March 1814 and so she would undoubtedly have noticed the Egyptian Hall that replaced the original Hatchards. It was an exhibition hall designed by Peter Frederick Robinson and housed the collection of Bullock’s Museum that had transferred from Liverpool to London in 1809.

Built in the ancient Egyptian style the hall opened its doors in 1812. Should she have visited it.

Jane would no doubt have been amused by its grand hall, which was a replica of the avenue at the Temple of Karnack.

Our ‘real’ walk should have started opposite Fortnum and Mason close to the Royal Academy of Fine Arts. In Jane’s time, this was Burlington House and one wonders if she might have caught a glimpse of James Gibb’s rather splendid colonnades at Burlington House as captured in a watercolour painting of about.1806–08.

The Burlington Arcade

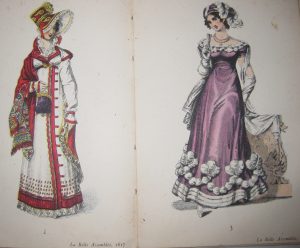

All coach passengers from the South and West of England would have been set down at the White Horse Cellar, which no longer exists and so Jane would have known this part of Mayfair. However, we made a quick detour up and down the Burlington Arcade. This would not have been there during Jane’s visits to London. It was built by Lord George Cavendish, younger brother of the 5th Duke of Devonshire, who had inherited Burlington House. The arcade was built on the side garden of the house and it is suggested that it was built to prevent passers-by throwing oyster shells and other rubbish over Duke’s wall and into his garden. It opened in March 1819. Originally there were 72, small, two storey units. Many of these have now been combined. Nonetheless, even though it façade is Victorian walking through the Arcade is like walking backwards into history. The architect Samuel Ware design remains as elegant today as it must have been then. This detour set the scene for our walk with the rows of small shops with their distinctive upstairs windows and jewellers’ shops glittering with precious, semi-precious stones and curios and shops selling scarves and shawls. Reminiscent of the converted India shawl made of cotton, silk, and gold threads were a sign of prestige in the fashion-conscious Regency period.

The Burlington Arcade just as it opened on a frosty morning.